Aphasia may be new to some thanks to Bruce Willis going public with his diagnosis. But many stroke sufferers and their caregivers know it well. I knew it well. I got a crash course in aphasia after Mommy’s first stroke. The stroke was on the left side of her brain, which is where the speech center is. After the stroke she could no longer control what she said.

Mommy was diagnosed with expressive aphasia. She could understand everything she heard, but she couldn’t control or access the words she needed to respond. Some stroke victims also fall victim to receptive aphasia, meaning they don’t understand what they’re hearing or experiencing. From the news reports about Willis, it seems like he has both.

After her first stroke, one way Mommy’s aphasia manifested itself was in the form of perseveration. She would repeat words she just heard someone say over and over, believing she was telling you something very clearly. If she had to go to the bathroom and someone on the TV just said “Beef Stroganoff,” she would insistently repeat “Beef Stroganoff. Beef Stroganoff. BeefStroganoff.” She sounded like a scratched record skipping over the same lyric over and over. She couldn’t stop herself or change what was coming out of her mouth.

As her caregiver, I watched as aphasia opened a door to the unknown, and I made it my job to protect her, whether I needed to or not. Our life-long mother-daughter bond helped me interpret for her, but it meant I had to be there for every visitor, every time a doctor came to examine her, and, in the early days, every therapy session. Otherwise, I would have no idea what was happening to her because she couldn’t tell me.

Through intense speech therapy, Mommy fought her way back. She regained her ability to speak enough to return to a new version of independence. But the second stroke was less kind. It held her firmly in its grip and never let go. The only words she could say were “NO,” — which she said a lot — “eminy,” and “anferny.” Any time I’d meet someone new on her care team, they’d ask, “Are you Emily?” “There is no Emily,” I’d reply. “She has aphasia. That’s all she can say.”

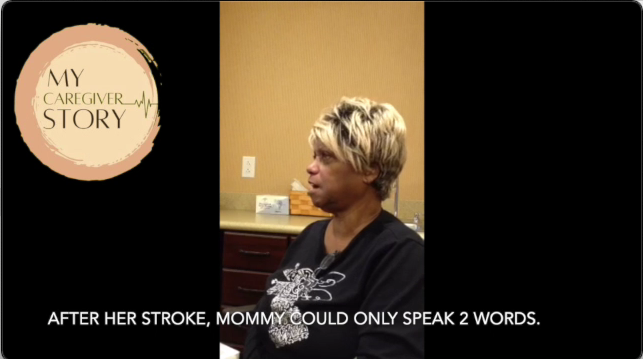

Interestingly, the ability to sing comes from the other side of the brain. When Mommy sang familiar songs, she was able to call up most of the correct words. I watch this video often. It taken after her second stroke. As uncomfortable as it was to see her this way, I got pleasure out of hearing her use real words, and I could tell she was proud.